Digitalisation and Technical Education

by Uwe Wieckenberg

We are in a time of disruptive change, the digital revolution. Artificial intelligence is likely to do many kinds of human work in near future. Robots will deliver parcels, drive cars, provide customer service, work in call centres, and possibly perform operations in hospitals. Digitalisation is by now already part of our private lives. Like all drastic changes, digitalisation exerts a very great pressure to change economic and social conditions.

If this digitalisation exerts a decisive pressure on all living conditions, so does it on education. How will digitalisation change our education and, above all, how must we shape education to prepare the young generation for a future that is largely uncertain and unknown?

In educational institutions we have relied so far on fixed curricula. These curricula define what students need to learn in order to achieve a certain educational goal. Unfortunately, these curricula are far too rarely revised and adapted to newer conditions.

In principle, we prepare students for what has gained validity in the past, but we do hardly prepare them for the future. This fact may be less serious for general education subjects. But for technical and vocational training, whether taught exclusively in schools or reciprocally in companies and schools, this fact is much more important.

For complex problems like the one outlined above, there can logically be no simple solution. The following are some considerations on how to approach the issue of digitisation in TVET.

Schools usually work in the field of formal education and are therefore bound by the requirements of the respective curricula. These curricula represent to a certain extent the minimum standard, but can be supplemented of course. One of these “additional subjects” - if this is not already defined in the curriculum – might be a comprehensive training in computer and internet skills and competencies.

So, the students learn how to use new technologies, especially computers in connection with the internet. However, this can only be the first step towards keeping up with the rapid pace of development in the IT sector.

Another feature of digitalisation is the constant availability of data. All knowledge tends to be available at all times and only a mouse click away. How does the “old” school, which is based exclusively on the imparting of knowledge, find itself in this scenario? Not at all, since knowledge no longer has to be taught exclusively by teachers. That is not to say that nowadays technical knowledge is no longer necessary. Of course, expertise is necessary, but no longer sufficient to meet the needs of digitalisation.

We need to enable students to deal with a new way of gathering information, to determine what information is reliable and how problems can be solved. For this new approach we need teachers who are less knowledge mediators than teachers who enable students to structure, validate and organise the available knowledge.

That's easier said than done, of course.

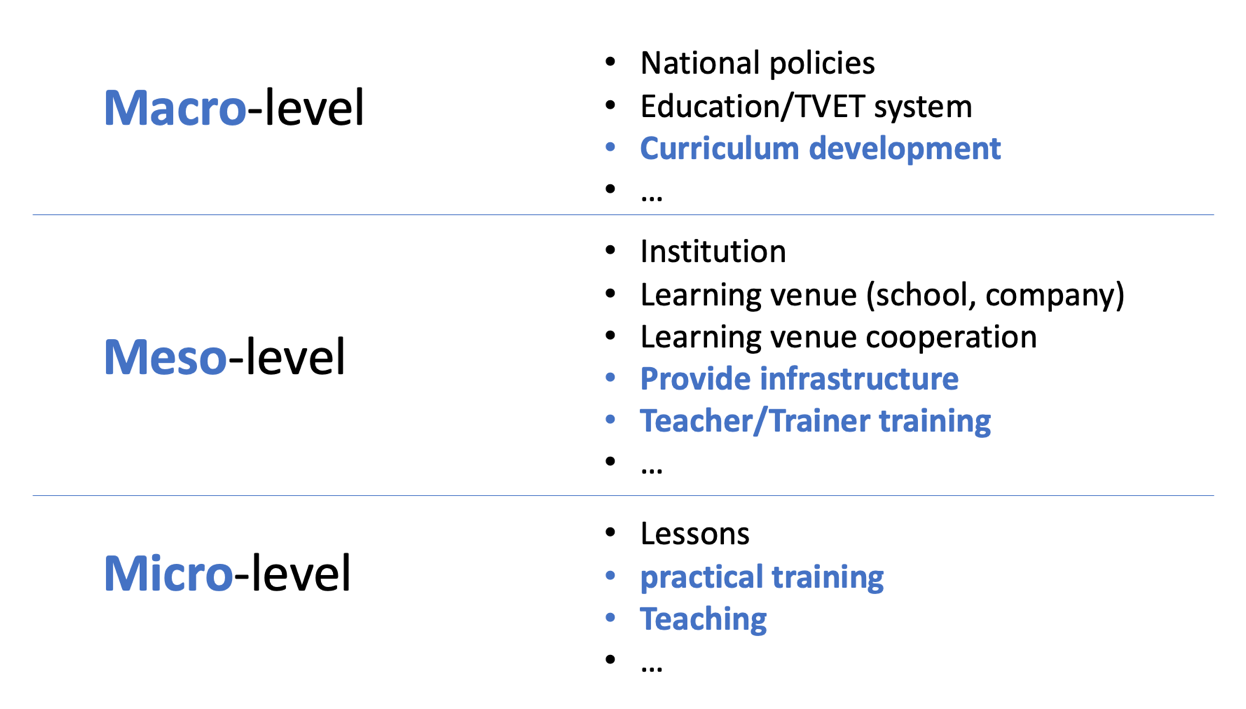

If we want to approach digitisation in TVET systematically, we should first distinguish between three analytic levels of the TVET system. The following diagram gives an overview of the three levels and the respective levels of action in TVET.

For successful digitalisation, all three levels should be included. Thus, steps towards digitalisation can only have a selective effect when we try to solve this issue only at the micro-level, i.e. in the classroom.

Micro-level: In the immediate teaching-learning process, the possibilities of transformation from analogue to digital teaching and learning can certainly be achieved with manageable effort. There should be a paradigm shift towards greater involvement of learners and emphasis on their role in the learning process, which has already been described frequently. “More learning and less teaching” could serve as a catchword here. Accordingly, the role of the teacher or trainer must change. Away from being a mediator of professional knowledge - knowledge is practically available all the time and everywhere - towards being an organiser of learning processes, an advisor to learners (what is wrong, what is right) and an evaluator of learning processes.

One of the characteristics of today's world is that professional knowledge is subject to constant change and modernisation. Our vocational curricula can only keep up with this rapid development with a very long time lag. Accordingly, students must be enabled to keep themselves up-to-date on their own - especially after completing their vocational training. Digitalisation and the use of digital offers is only one of several means here.

Meso level: It is somewhat more difficult to get a grip on digitisation on the part of the institution (school, training provider, company), as this usually involves greater expenditure on the IT infrastructure and above all on the training of teachers. If the in-service training of teachers is not implemented systematically and comprehensively, digitalisation is exclusively dependent on motivated and experienced teachers.

Macro level: Finally, there is the policy level. This is where responsibility lies for current curricula in formal education, which have to be continuously developed and revised more frequently than in the past.

Teachers teach what is written in the curriculum and students learn what is required in the examination. If topics of digitalisation and the competences needed for it are not included in the curriculum and the examination requirements, no steps towards digitalisation can be expected.

How to start?

All beginnings are difficult, of course. In only a few cases - if any - digitisation in TVET is systematically approached from all three levels. Very limited financial resources come on top.

It seems easiest if we start at the lower level, i.e., in the daily classroom. Here it is important to introduce the students to the new resources, which they mostly already know from the private sphere. Work with the Internet must be integrated in "normal" face-to-face teaching. Besides the textbooks and the teacher's input, the Internet is just another source of technical information. Of course, the students must be able to deal with the variety of information and to separate useful from less useful or even wrong information. In addition, there are a variety of teaching methods that involve students more actively in learning and do not leave them passive as mere recipients of knowledge, as is often the case nowadays.

When it comes to skills training, digitalisation certainly plays a different role. Virtual and augmented reality applications are worth mentioning here. What can hardly be replaced, however, is practical hands-on training in the workshop or in the company.

When we start with digitisation at the lower level, cooperation and coordination between schools and companies should be strengthened in order to move together in the same direction. In the past, this learning venue cooperation was unfortunately often neglected.

Furthermore, it is becoming increasingly important to equip students with future-ready skills. What used to be called "key competences" in TVET is now labelled "21st century skills" or simply "future skills". This actually always means the same competences in the methodological, social and personal areas.

We have to combine the teaching and training of subject-specific competences with different teaching and learning methods in order to promote understanding on the one hand and the applicability of what is learned on the other.

This is also one of the conclusions reached by UNESCO-UNEVOC in the study on “Trends shaping the Future of TVET teaching”:

“As digitalization and automation are changing the world of work, demand for transversal and applied skills are most likely to grow in the next 10 years.”